Mercy Means Never Having to Say You’re Sorry?

“Why do they only have 45 minutes for confession?” asked my Protestant dad when I was home over the holidays. “Well,” I tried to explain, “Most church-goers don’t go to confession that often. They don’t really think they’re doing anything wrong.”

“Why do they only have 45 minutes for confession?” asked my Protestant dad when I was home over the holidays. “Well,” I tried to explain, “Most church-goers don’t go to confession that often. They don’t really think they’re doing anything wrong.”

A senior deacon from one of the first classes of people trained in the post-Vatican II era told me that the deacons were instructed to excise the words “mortal sin” from their vocabulary. Or as one pre-Cana teacher asked me with wide-eyed honesty after teaching her class that they didn’t really have to go to Sunday Mass as long as they had a personal relationship with Jesus, “Do Catholics believe in mortal sin any more?”

I choked out with admirable self-aplomb, “Yes, we do have an obligation to attend Sunday Mass and yes, we do believe in mortal sin. It’s in the Catechism.”

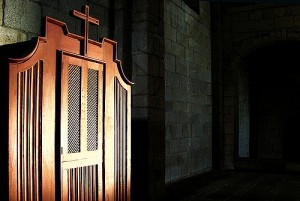

Welcoming people and accepting them with love is one thing. Throwing the Catechism (and centuries of Church teaching) out the window or using it as a doorstop rather than a reference manual is quite another. The “I’m okay, you’re okay” approach avoids offense and smooths ruffled feathers. But if I’m okay and you’re okay, then why would God need to forgive us for anything? Why would we need the confessional?

In the mind of modern man, we don’t. That’s why parish confession times last 45 minutes, and the line of people who show up often vacillates between few and none.

This obvious trend is what makes conservative Catholics really, really nervous when Pope Francis preaches about mercy. “Mercy” looks like carte blanche for bad behavior as long as we’re still basically good people. Or at least better than our gossipy neighbor or mean boss or neglectful spouse. I mean, compared to them, what have we done that’s really so bad? What do we have to say sorry for?

According to one Italian priest, Pope Francis’ pontificate is making things go from bad to worse. That priest has observed “not only a further drop in the practice of sacramental confession, but also a deterioration in the ‘quality’ of the confessions themselves.”

He gave one example where he was encouraging a repeat offender to repent and resolve not to commit the same sin in the future. The penitent answered, “Mercy knows no limits! … I am here only to have what everyone deserves at least at Christmas: to be able to receive communion at midnight! …Who are you to judge me?”

In another example, when the priest imposed a penance, the penitent refused to perform it on the ground that “no one must ask for anything in exchange for God’s mercy, because it is free.”

Without a doubt, these two penitents lacked a basic understanding of what sacramental confession is all about. The Catechism explains: “The movement of return to God, called conversion and repentance, entails sorrow for and abhorrence of sins committed, and the firm purpose of sinning no more in the future” (CCC 1490). This is why Mafia enforcers can’t go to confession every weekend and be absolved of their sins as murderers-for-hire. They’ve got to intend never to do it again — to “go and sin no more.”

“The imposition and acceptance of a penance” is also an essential element of sacramental confession because it repairs the harm caused by sin and encourages the penitent to live in a more Christian way (CCC 1480, 1494). Penance requires us to put our money where our mouth is, so to speak. If we’re truly sorry for the damage our sin has caused to God and to others, then we can prove it by making amends.

Although the anonymous Italian priest implicates Pope Francis as the guilty party, it’s hard to lay the blame squarely at our pontiff’s feet. I’m sure people say outrageous things in the confessional all the time. “A priest is surprised by nothing,” says my husband. Much like a psychiatrist, a priest has heard it all.

The pastor in the little Virginia town where I grew up had very different stories to tell about Catholics’ reaction to Pope Francis’ call for mercy. As this country priest traveled throughout his rural territory to offer confession this past Advent, he saw many more people showing up in church. They told him that they came because of Pope Francis.

Francis made them want to get closer to the Church and closer to the Church meant closer to the sacraments, closer to the confessional. “Pope Francis tells you to walk through the holy door during this Jubilee Year of Mercy. Well, I tell you that you can accept that invitation by walking through the holy door of the confessional,” the pastor said in his Christmas homily.

Pope Francis has just given the world a close-up view of his interpretation of mercy in his new book The Name of God Is Mercy, released this week. Confession does involve “a certain amount of judgment,” acknowledged Pope Francis, and sometimes a priest cannot grant absolution.

Pope Francis gave the example of his own niece, civilly married to a divorced man who hasn’t obtained an annulment of his first marriage yet. His niece’s husband went to confession every Sunday before Mass, telling the priest, “I know you can’t absolve me but I have sinned … please give me a blessing.”

Pope Francis praised his niece’s husband as “a religiously mature man,” and added, “if the confessor cannot absolve a person, he needs to explain why, he needs to give them a blessing, even without the holy sacrament. The love of God exists even for those who are not disposed to receive it.”

Sin is real, and Pope Francis isn’t afraid to preach about it. Sin hurts: “sin is more than a stain. Sin is a wound; it needs to be treated, healed.” Shame is a grace: “it is good, positive, because it makes us humble.” Shame for sin leads a penitent to the confessional and into the arms of God: “he ought to feel like a sinner, so that he can be amazed by God. In order to be filled with his gift of infinite mercy, we need to recognize our need, our emptiness, our wretchedness.”

Would Pope Francis agree that mercy means never having to say you’re sorry? Not a chance.