The Agony of Holiness

Holiness is not merely faith, it is not merely virtuous behavior, it is not merely serving others, and it is not merely acts of piety. Holiness at its core is the belief that we were made to share in the life of the Holy Trinity coupled with the desire and the determination to act in such a way that draws us ever closer to the God who loves us and desires our full return to Him.

Holiness is not merely faith, it is not merely virtuous behavior, it is not merely serving others, and it is not merely acts of piety. Holiness at its core is the belief that we were made to share in the life of the Holy Trinity coupled with the desire and the determination to act in such a way that draws us ever closer to the God who loves us and desires our full return to Him.

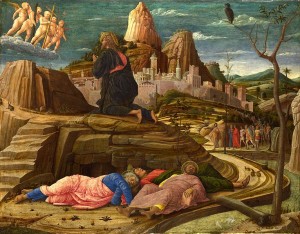

This is precisely what Jesus modeled for us in the Garden of Gethsemane.

Then Jesus came with them to a place called Gethsemane, and said to the disciples, Sit here while I go and pray over there.” And He took with him Peter and the two sons of Zebedee, and He began to be sorrowful and deeply distressed. Then He said to them,”My soul is exceedingly sorrowful, even to death. Stay here and watch with Me.” He went a little farther and fell on His face, and prayed, saying, “O My Father, if it is possible, let this cup pass from Me; nevertheless, not as I will, but as You will.” (Matthew 26:36-39)

Despite the perfect holiness that existed in His divine nature and divine will — meaning that, as the Second Person of the All-Holy Trinity, Jesus was the both the architect and the living reality of the plan that He, God, had set forth for the world — Jesus also experienced the agonizing vicissitudes of a human nature and human will. In other words, even though Jesus was God, He was also a man who felt the crippling weight of the divine plan that had been foisted upon His shoulders. Consider how this unfolds in the passage from Matthew.

First, Jesus prayed. His human nature and human will still had to be nourished by His Father in heaven. Second, Jesus asked for the company of His closest friends. Since He was in such a sorrowful state over what awaited Him, He asked for company so as not to be totally alone. Third, Jesus felt the weight of His suffering so deeply that it felt like death. His fear and torment even caused Him to fall on His face. Fourth, Jesus begged His Father to alleviate from Him the suffering that was coming. His words, filled with anxiousness and distress, were a final grasp at the false hope that some other path might be taken. Fifth, and finally, He relented and gave Himself over to the plan of God.

When considering this course of events most of us can relate to the need for prayer, to the need for close family and friends in our darkest hours, to the kind of suffering that can form a shroud over our whole life, and to prayers that beg for the alleviation of the weight of sin and pain. But what separates us from Jesus was His absolute and personal commitment to following the will of God… even to the point of death.

Remember: this chain of events in the Gospel of Matthew does not arise from Christ as God, but from Jesus as human. This is vitally important on this Great and Holy Friday because not only do we witness Jesus willingly cross into the tomb of death, but also because it forces us to ask the ultimate question: “Will I follow Him into the grave?”

Sadly, it is increasingly difficult to ask such a question of ourselves, let alone anyone else, because it simultaneously forces us to ask what it means to be truly good… what it means to be holy.

The impenetrability of doing so, of course, is derived from a modern American culture that is increasingly antagonistic toward belief in God, toward religion, toward Christianity in general and certainly toward Catholicism and Orthodoxy in particular. Making matters worse, are the efforts of an increasingly progressive, increasingly modernist wing of the Church where far too much emphasis is placed on social justice. While these activities, at one level, are both necessary and laudable, they replace holiness-as-union-with-God with holiness-as-human-action. The fact of the matter is that the atheist or agnostic is just as good at feeding the hungry and clothing the naked.

Therefore, the true Christian must bring Christ Jesus. That means we must bring to people our holiness — our deepest commitment to following the will of God throughout our lives. Starting with ourselves, our families and friends, our co-workers and then to those strangers who cross our paths, we must show that our very own prayers are transforming our lives. We must show them that we are the transfigured humanity of which Jesus spoke.

To do this, our public prayer and our personal prayer must exude long after we have left our Churches, chapels and prayer corners. In other words, before people even view our charity toward others they must encounter a deep sense of worship in us, an attitude of prayer that never subsides and a countenance that transverses the natural and the supernatural.

God wants us to become like the angels. The angels only glorify God. This is their prayer, glorification of God and nothing else. The glorification of God is a very subtle matter; it eludes human criteria. We are very material and earth-bound, and for that reason we pray to God in a self-interested manner. We ask Him to order our affairs, to help our businesses do well, to protect our health and to safeguard our children. But we pray in a human way and with self-interest. Doxology is prayer without self-interest. The angels do not pray in order to receive something; they are selfless. God also gave to us the possibility for our prayer to be an unending doxology, an angelic prayer. This is where the great secret lies. When we enter in this prayer, we will glorify God continually, leaving everything to Him… (Wounded by Love: The Life and the Wisdom of Elder Porphyrios, p.133).

When we glorify God continually and when we leave everything to His will — this, of course, is true holiness — but it is also the nature of the agony that Jesus felt in the Garden.