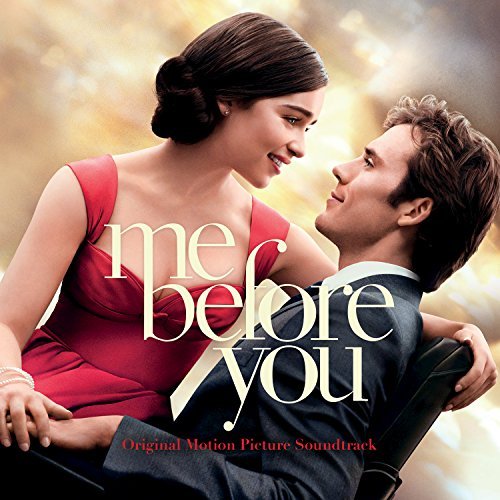

Movie Review: Me Before You

WARNING: I TELL YOU THE END OF THE FILM IN THE NEXT SENTENCE.

Due to the serious subject matter of the film Me Before You (euthanasia), and the fact that most people already know how the movie ends (euthanasia), combined with the fact that the film is based on a novel by the same name that came out in 2012, this entire movie review will be one big spoiler. Advance at your own risk.

Due to the serious subject matter of the film Me Before You (euthanasia), and the fact that most people already know how the movie ends (euthanasia), combined with the fact that the film is based on a novel by the same name that came out in 2012, this entire movie review will be one big spoiler. Advance at your own risk.

This British film maintains the light air of a romantic comedy throughout, overlaid with tear-jerking moments and the sweetest violins. Unlike a Jodi Picoult story that explores controversial issues as serious dramas, Me Before You more or less accepts assisted suicide as a valid option and a part of life (irony intended).

Suicide, in fact, is sexy and sweet. As sexy as a gorgeous, wealthy, young quadriplegic, Will (Sam Claflin from Hunger Games), and as sweet as his new, bubbly, Kimmy-Schmidt-like caretaker, Lou (Emilia Clarke from Game of Thrones). And it’s not just our main characters that are comely, the actual moment of Will’s demise is preceded by jokes, kisses, smiles and lots of sunshine pouring in the window — all set to swirling, swelling strings.

The film starts off in a sort of saccharine, almost overly simplistic way: from Will’s insanely perfect life with his girlfriend to Lou’s insanely ditzy existence. But this caricature-ish, one-dimensionality never quite inflates into two or three dimensions, even at the most poignant moments.

Lou eventually gets under the embittered and sarcastic Will’s skin with her perpetually cheery, optimistic and endearing demeanor, coupled with her highly original fashion choices. The dialogue and gentle sparring is genuinely witty and charming. The plot machinations are funny.

At one point, while the “superior” Will is trying to school Lou about life, Lou comes back at him with a knowing description of how the type of upwardly mobile woman Will is encouraging her to be actually fares in the end. Lou is not as dumb as she looks.

Lou finds out about Will’s plan to undergo euthanasia in Switzerland in only six months’ time. She and his mother (who also is hoping along with Lou that he’ll change his mind) put their heads together to try to get Will to enjoy life again, get out and do things as best he can in his motorized wheelchair. Will obliges, but more for Lou than for himself. However, he is thoroughly enjoying her company.

When Will finally tells Lou about Switzerland, she tells him she already knows. Will then begins to lay out before her his reasoning. He liked his old life. A lot. (He was also very athletic.) Is Will trying to say what is said of dementia patients in order to euthanize them? That he’s not really “himself” anymore? Sorry. The “self” remains till the last breath — no matter what condition the mind or body is in.

Will doesn’t mention his prognosis as part of his justification for ending his life, but Lou gets that information from others: Will’s main problem is his spinal cord which can’t be fixed. He’s on lots of medications and is weak and vulnerable to infections. He has recurring pneumonia. He is often in pain. In his nighttime dreams he is active once again, but wakes up screaming when he realizes he’s paralyzed.

In Me Before You, quality of life is more important than life itself. Will wants his old life back. He resists change (as horrible as the changes in his life are) and moving forward. But who can ever “have their old life back”? And for how long? In a few more decades, he will be elderly and unable to do all things he loves to do, anyway.

A brief discussion about the morality of assisted suicide is put in the mouth of Lou’s cross-wearing, grace-at-meals-praying mother: “There are some choices we don’t get to make! It’s no different from murder! You can’t be a part of it,” she tells her daughter.

Lou is not sure if she did the right thing by refusing to go with Will to Switzerland to be with him when he dies as he had asked her. Lou’s Dad simply says: “We can’t change people.” (True enough.)

Lou had tried so hard to change Will’s mind. When Lou asks in return: “Then what can we do?” Dad says: “Just love them.” Her Dad instead encourages her to join Will and his parents in Switzerland.

The title is curious. Who is “me”? Who is “you”? Although Lou begs Will not to go through with his lethal plan, promising to stay with him, Will tells her that his mind has been made up from the beginning and that he has never wavered, not even for her. He will not stay alive for her.

She brought some joy into what he has determined to be the end of his life, and he did his part trying to bring her out of her shell and get her to dream big. But this eleventh hour fling was only in the context of a promise he made to his parents: he would give them only six more months.

The sacrifice (even though Lou is a well-paid employee of Will’s mother) seems to be all on Lou’s part. This does not seem to be a true, reciprocal love story. If he had stayed alive for her, it would have been. You can’t be in love with a ghost and share life with a ghost (all apologies to Patrick Swayze). Will also hints that because they won’t be able to have a married life with sex and children, she doesn’t know for a fact that she won’t have regret in the future for having stayed with him.

What is the point of this book/movie? Why was it created? To make euthanasia more palatable? “It’s his choice” is stated over and over again. Yes, of course, suicide has always been a choice, an option. A very sad and tragic one, one that people choose only in utmost desperation, and one that humanity has always tried to talk and help its constituents out of.

Will says: “I’m not the kind of man who can accept this.” (Who can really “accept” a tragedy such as quadriplegia?) And yet people do “accept” it all the time. Look at the brilliant and drastically compromised Stephen Hawking (who suffers from ALS) who presses on with humor and an indomitable will to live, still contributing to the world of science).

There is no mention of God as the master of life and death. No mention of going back to God at death. (Although there is a belief in some kind of an afterlife when Will tells Lou he will be right by her side all through her life. Which is also strangely creepy. What if she gets married?) No mention of what dying naturally would be like (most likely he will diminish irreparably in just a few years and die naturally then anyway). No mention of redemptive suffering: the fact that suffering purifies us and can be offered up for others. No mention of the fact that we go on living till the last gun is fired.

What if there are still important lessons for him to learn, indispensable bits of living still to be lived? Others who need to come in contact with him, whose lives he can grace? And of course, as believers, we would want to grow daily in our relationship with God as much as possible on this earth before we leave it.

Me Before You has to be classified as a pro-euthanasia film. It’s like a sugar-coated poison pill. Our world is on a slippery slope to justifying suicide for just about any reason.

What happened to helping each other live, not die? What happened to hope? Does this mean we shouldn’t stop people from jumping off ledges? After all, it’s their choice. “Hey buddy! Hold it right there! We respect your choice, and we don’t really care if you die or not, so just hold on and we’ll get you a physician….”