Blessed John Henry Newman and the Conscience

Moral relativism bothers me for numerous reasons, but the greatest annoyance I have is relativism’s consistent use of illogical reasoning and justification. Besides selfishness, relativism’s only consistent attribute is being illogical. I find this frustrating because several friends buy into relativism lock, stock, and barrel without a second thought.

By illogical I should say I mean kindergarten logic, which is in itself illogical. “I want what I want because I want it and you cannot tell me no because I want it and therefore you cannot deprive me of what I want because I want it.” Umm…I don’t..uh..what? Someone get me off this not-so-merry-go-round.

Along with claims to unfettered desires for worldly experiences and goods, without a thought to consequences or an objective right and wrong, moral relativists will make an old claim to conscience. Catholics and Protestants since the sixteenth century have also thrown down claims of the superiority of conscience and its guidance, and yet held divergent views on central tenants of faith.

Conscience has been the supreme trump card everyone played. If I were a betting man, however, I would wager a hefty sum that very few Christians, atheists, and agnostics today could define exactly what they mean by ‘conscience’. The ambiguous use of the word means someone can use ‘conscience’ to defend anything, or at least attempt to defend anything, however groundless the position may be.

The Guiding Light

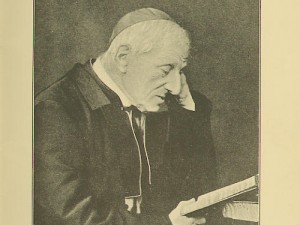

Blessed John Cardinal Newman writes;

Conscience does not repose on itself, but vaguely reaches forward to something beyond self, and dimly discerns a sanction higher than self for its decisions, as is evidenced in that keen sense of obligation and responsibility which informs them. And hence it is that we are accustomed to speak of conscience as a voice,…imperative and constraining, like no other dictate in the whole world of our experience. (Essay in Aid of a Grammar of Assent)

To make an appeal to conscience is, in a concrete sense, an appeal to God’s guidance and supreme authority. To admit God’s role as such is to say our desires and decisions are subject to a higher judgment than our personal preferences. Without this understanding, appealing to conscience is no different than saying “because I said so,” which, frankly, only God has claim to.

If, as is the case, we feel responsibility, are ashamed, are frightened, at transgressing the voice of conscience, this implies that there is One to whom we are responsible, before whom we are ashamed, whose claims upon us we fear…These feelings in us are such as require for their exciting cause an intelligent being: we are not affectionate towards a stone, nor do we feel shame before a horse or a dog; we have no remorse or compunction on breaking mere human law: yet, so it is, conscience excites all these painful emotions…; and on the other hand sheds upon us a deep peace. (Newman, Essay in Aid of a Grammar of Assent)

Our conscience, then, is not a tool to justify our every decision. Newman draws attention to two important aspects of our conscience. First, the more we listen to our conscience our understanding of its guidances is proportionately increased. “And…as we listen to that Word, and use it, not only do we learn more from it, not only do its dictates become clearer, and its lessons broader, and its principles more consistent, but its very tone is louder and more authoritative and constraining.” Thus, the conscience is a not a green light to all desires, but a way of discerning the proper course.

Second, when the conscience’s whisper is heard and we have begun to overcome the confusion between God’s guidance and our own prideful and selfish ways, we will long for something more, “so that the gift of conscience raises a desire for what it does not itself fully supply. It inspires…the idea of authoritative guidance, of a divine law; and the desire of possessing it in its fullness.” The proper disposition, then, is one of humility and charity to look beyond ourselves.

Trusting the Church

What we search for in discernment, vocations and otherwise, is a deep, abiding peace. Our conscience causes internal disruptions or joy depending on our relation to God’s path. When someone, say a priest or the Church’s teachings, challenges us in charity (Matt 7:1-5, 18:15-17, 1 Cor 5:9-13) to alter our ways and our immediate impulse is to balk we should question why. My first guess, for myself, is always either ignorance, pride, or both. If the Church states X, Y, and Z are all mortal sins, those sins which break one or more of the Ten Commandments in some way, and we insist the Church is wrong, what are we saying?

Think of this. Holy Mother Church is who first told us about the man called Christ and His Word. This man, in fact, was God and is both truly God and truly Man. Not only that, but He came into the world willing accepted humiliation and crucifixion, and died for the sins of men that they might attain salvation.

If you accept this Good News, what else are you accepting? God’s abiding love of you, the nature of God and his relationship to creation, an answer to the supreme question, “why are we here?”, the promise of Heaven and the reality of Hell, His promise to remain with us until the end of the age (Matt 28: 16-20), and so much more. We are willing to trust the Church’s teachings about eternity, and yet we are unwilling trust the Magestrium’s guidance in matters like social teachings. Simply put, give me Heaven, but keep the rest.

The convert comes, not only to believe the Church but also to trust and obey her priests, and to conform himself in charity to her people….Moreover he comes to the ceremonial, and the moral theology, and the ecclesiastical regulations, which he finds on the spot where his lot is cast. And again, as regards matters of politics, of education, of general expedience, of taste, he does not criticize or controvert. And thus surrendering himself to the influences of his new religion, and not risking the loss of revealed truth altogether by attempting by a private rule to discriminate every moment its substance from its accidents, he is gradually so indoctrinated in Catholicism, as at length to have a right to speak as well as to hear. (Newman, Certain Difficulties felt by Anglicans in Catholic Teaching Considered)

Newman’s intellect, prayer life, and conscience led from the Anglican (Church of England) to the Catholic Church. His conversion cost him his position at Oxford where he had helped begin the renewal of the Church of England through what became known as the Oxford Movement. Many of his friends and family disowned him (a not uncommon theme amongst converts) for a long while when Newman made his conversion public.

His social reception into the Catholic Church was marred by mistrust and his past harsh words against the Catholic Church. But, through this, Newman continued to work to build up the Church in England, including establishing the Birmingham Oratory and publicly supporting Catholic education and the re-establishment of Catholic Sees in England.

Written upon Our Hearts

“[We] may silence [our conscience] in particular cases or directions, [we] may distort its enunciations…[we] can disobey it, [we] may refuse to use it; but it remains.” Without Jesus Christ, the moral law is not inscribed on our hearts by God but superimposed by society. Without a divine law, without God, there is no right and wrong in any sense other than cultural or societal, which is to say morality is subjective.

The word ‘conscience’, then, has very little meaning.I can be for or against whatever I wish, and you cannot say otherwise. Giving offense is merely a matter of perspective and ego. This, also, completely discounts the reality of sin and its impact upon the human family.

To see truly the cost and misery of sinning, we must quit the public haunts of business and pleasure, and be able, like the Angels, to see the tears shed in secret, -to witness the anguish of pride and impatience, where there is no sorrow, -the stings of remorse, where yet there is no repentance, -the wearing, never-ceasing struggle between conscience and sin, -the misery of indecision, -the harassing, haunting fears of death, and a judgment to come,….Who can name the overwhelming total of the world’s guilt and suffering. (Newman, Oxford University Sermons)

We must nourish our conscience as much as our soul. We cannot take our conscience for granted as if we will always clearly hear its voice uncorrupted by pride, secularism, and selfishness. If our conscience is guiding us towards the truth of the matter, we must keep our eyes wide open and unclouded.

Of the two, I would rather have to maintain that we out to be begin with believing everything that is offered to our acceptance, than that it is our duty to doubt of everything…we soon discover and discard what is contradictory to itself;…that when there is an honest purpose and fair talents, we shall somehow make our way forward,…Thus it is that the Catholic religion is reached, as we see, by inquirers from all points of the compass, as if it mattered not where a man began, so that he had an eye and a heart for the truth. (Newman, Essay in Aid of a Grammar of Assent)