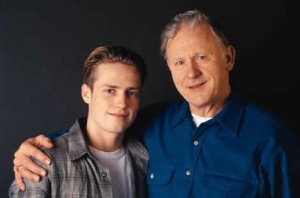

[1]When you were a teen, did your dad ever talk to you about what it is to be a man? Probably not. And if he did, did you listen? Probably not.

[1]When you were a teen, did your dad ever talk to you about what it is to be a man? Probably not. And if he did, did you listen? Probably not.

When I was growing up I found that my dad was hardly ever there for me. He was a ‘good father’ by being at work, providing for the family. He took his fatherly responsibilities seriously, just like millions of other dads. But when he was home, did we talk much during my teen years? No. Did we ‘connect’? No. We were effectively strangers who lived under the same roof. It appears that this is normal in millions of homes today too.

As for growing into a young man, I was left to figure it all out for myself. And I struggled. But I would never let anyone know because that would be seen as weak and unmanly. So I pretended to be what I thought a man was supposed to be.

Looking back, I had absolutely no idea what I was doing. I didn’t even know what I didn’t know! Yet, somehow this was all normal. Almost all guys went through the same thing.

We didn’t talk. Our dads didn’t talk. And their dads talked even less.

In direct contrast, transitioning from boyhood to manhood is a vital, guided step in so-called primitive, tribal societies. In those communities, boys grow up around male company; they live and work with their fathers, brothers, uncles, grandfathers and all the other men in their villages.

These boys learn how to be good, responsible men from an early age.

In fact, it’s common practice in many tribal societies for young boys as young as seven or eight to look after the villages’ most valuable asset; the livestock. These goats, sheep and cattle represent the entire wealth of a village, yet their safety and well-being are entrusted to little boys.

Would that be allowed to happen in the West? There’s no way such activity would pass a health and safety risk assessment! Wild animal attacks, the potential for being trampled to death by stampeding goats is far too risky.

Here, young male adults are no longer taught what they need to know about their future lives as men. They still have to figure it out for themselves. And they are under far more pressure than ever before.

Out-performed by girls at school, saddled with University tuition debt, unable to afford to leave home and a chronic lack of employment opportunities has resulted in so many young guys feeling lost, isolated, trapped and even discarded by society before they’ve even started their lives as men.

Is it any surprise that the biggest cause of death among young men is now suicide? The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention claims that a young man is three to four times more likely to commit suicide than a young woman. Putting that into perspective, more young men die of suicide in North America than get killed in combat fighting for their country in conflict zones around the world.

This was brought home to me recently when I heard of a distraught dad whose intelligent, seemingly happy son had committed suicide just days before his 18th birthday.

Too many young guys feel as though they are not being taken seriously. They are really struggling.

“But they won’t listen.” You might say. That’s partially true. They won’t listen to their parents any more.

When is the last time you really listened to your own parents, your partner or your children without jumping in to tell them why they are wrong about whatever they said? Why their fears are unfounded or silly? And then, with the best of intentions perhaps, do you then tell them what they ‘must’ or ‘should’ do?

If so, that’s precisely why young men don’t listen to their parents!

Instead, just listen. Don’t offer advice unless it is specifically requested. My book is designed to provide an independent bridge between dads and their teenage sons to get them talking and listening more to each other about what it is to be a man. Whether you use my book or not, many more of these really important conversations must happen. Society so desperately needs more responsible men.