The works of William Shakespeare abound with the truths of the Catholic faith. Especially in his later plays (often called the “romances”), Shakespeare focuses his poetic imagination on the mysteries of grace, redemption, and resurrection. The results are surprising, strange, and wonderful stories that can do far more than entertain us. When he needed to teach his followers something important, our Lord told stories. This suggests that we are created in such a way that we can learn truth through stories, and that we can come to know our Lord through listening to stories.

Advent begins tomorrow and one way to prepare for Christ’s coming is to meditate on the story of his Nativity. Besides the Gospel accounts, one of my favorite stories to read during this season is Shakespeare’s play the Winter’s Tale. The story Shakespeare tells illuminates aspects of the Nativity story in a way that points me back, with increased wonder, to the Gospels and ultimately to our Lord Himself.

Like the story of the Nativity—which really begins with the story of the fall—the Winter’s Tale begins with a descent: the tragic fall of King Leontes. Leontes and Hermione, king and queen of Sicilia, are hosting King Polixenes of Bohemia, Leontes’ childhood friend. Great love exists between them all, but Leontes becomes suspicious of Hermione and Polixenes and convinces himself that the two are having an affair. The suspicion is unfounded—Hermione and Polixenes are clearly pure in their love and committed to the king’s own good—but none of this matters to Leontes. He accuses his pregnant wife of adultery, tries and condemns her, ignores the protest of his friends, blasphemes against the gods, and indirectly causes the death of his young son who cannot bear the false accusations against his mother.

The whole terrible fall happens suddenly in the beginning of the play with Leontes doubting the intentions of those who truly love him. Acting on this doubt, he makes rash and disastrous choices that cost him nearly everything. Sound familiar?

[The serpent] said to the woman: Why hath God commanded you, that you should not eat of every tree of paradise? And the woman answered him, saying: Of the fruit of the trees that are in paradise we do eat: But of the fruit of the tree which is in the midst of paradise, God hath commanded us that we should not eat; and that we should not touch it, lest perhaps we die. And the serpent said to the woman: No, you shall not die the death. For God doth know that in what day soever you shall eat thereof, your eyes shall be opened: and you shall be as Gods, knowing good and evil. (Genesis 3 [2])

Doubt God’s word; doubt his intentions; suspect that one who truly loves you is actually deceiving you and withholding some good from you—this is how the evil one tempts Adam and Eve to their destruction and these are the doubts that undo Leontes.

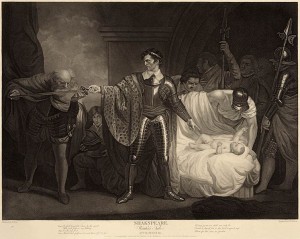

In a tragic turn, the queen Hermione gives birth to her baby girl while in prison awaiting trial. The king cruelly rejects his daughter as the “bastard” of Polixenes and orders one of his lords to take the child outside his realm and abandon it. The lord, Antigonus, obeys the king and sails off with the newborn whom he names Perdita (Latin for lost one). As soon as Antigonus abandons the baby, a savage bear chases him off stage and kills him. At the same moment, a storm sinks the ship Antigonus sailed in and drowns the crew.

Back in Sicilia, Leontes finally realizes his errors, but it’s too late. His newborn daughter has been abandoned in the wild. His slanderous words have effectively killed his son. When she hears of her son’s death, the queen swoons and also appears to die. Polixenes and Camillo, Leontes’ most trusted servant, flee in fear for their lives. Like an outcast from Eden, Leontes loses almost everything. Yet one seed of hope remains. Leontes receives a pronouncement from the Oracle at Delphi with these words from Apollo (the play is set in pagan times):

Hermione is chaste;

Polixenes blameless; Camillo a true subject; Leontes

a jealous tyrant; his innocent babe truly begotten;

and the king shall live without an heir, if that

which is lost be not found.

Shakespeare structures his story so that the fate of the entire kingdom depends upon one innocent babe, the truly begotten and rightful heir. Where have we heard that before?

Behold thou shalt conceive in thy womb, and shalt bring forth a son; and thou shalt call his name Jesus. He shall be great, and shall be called the Son of the most High; and the Lord God shall give unto him the throne of David his father; and he shall reign in the house of Jacob for ever. (Luke 1 [3])

When the Lord God of Hosts came into this world, he came as defenseless babe, born in a stable to a humble virgin married to a carpenter. This union of power and humility—so central to the Catholic faith—appears frequently in Shakespeare’s works, but it is especially clear here in the Winter’s Tale with the nativity of Perdita.

Perdita, the innocent child on whom the fate of the kingdom rests, lies abandoned in the wild. And who should first find and adore the child but a shepherd! The scene is comical, simple, sweet, and very down-to-earth—very like how our Lord’s Nativity must have been. The funny old shepherd appears, looking for some lost sheep of his and grumbling about the impertinence of youth when suddenly:

. . . what have we here! Mercy on ‘s, a barne a very

pretty barne! A boy or a child, I wonder? A

pretty one; a very pretty one: sure, some ‘scape . . .

The shepherd finds the child who will save the kingdom and whose name means the lost one while out looking for lost sheep—a subtle but profound touch which is so typical of Shakespeare and which points back to the mysterious divine artistry that first sent shepherds to adore the newborn Lamb of God.

The shepherd’s son then enters and tells his father he has seen a bear kill Antigonus and a storm sink the ship. The shepherd exclaims: “Heavy matters! heavy matters! but look thee here, boy. Now bless thyself: thou mettest with things dying, I with things newborn. Here’s a sight for thee,” and he presents the child.

Like the shepherds in Bethlehem, these shepherds of Shakespeare find themselves in the presence of something that fills them with awe. And while the fallen world may be going in one direction—to meet with things dying—these humble shepherds meet with something “newborn”—something life-giving. Although he’s not quite as eloquent, the old shepherd reminds me of Simeon meeting the infant Jesus and it helps me to picture how tenderly that patient old man must have cradled the Christ-child in his arms.

I don’t want to spoil the ending of the Winter’s Tale, so if you want to know what happens to the shepherds and Perdita and Leontes’ kingdom, you’ll just have to read it yourself [4] (and you should, because there’s a surprise ending!). But as a final point, I want to clarify that none of this is to suggest that the Winter’s Tale is really just an allegory for Christ’s Nativity. It’s not about decoding which character in the play stands for which character in the Gospels. Rather, I would suggest that Shakespeare’s works, and especially the late romances, are fruits which grow organically from a very sacramental, Catholic understanding of the world. For this reason, it can be very fruitful to us to read Shakespeare in the light of Catholic scripture and tradition. His stories contain much worth meditating upon and they constantly point back to the Author of all our stories.