[1]Et verbum caro factum est. That’s Latin for “And the Word became Flesh.”

[1]Et verbum caro factum est. That’s Latin for “And the Word became Flesh.”

What is this ‘word’? The word, the word, the bird is the word? Hardly an early sixties one-hit-wonder. The Word of which I speak has more staying power than even rock ‘n’ roll. Even more than the Strolling Bones and they’ve been around a long time. Keith Richards is the Lazarus of rock.

The Word of which I speak is God’s revelation to the world.

A long time ago from a galaxy far, far away God began to speak to our ancestors through the prophets. Since 6 BC he has spoken to us through his Son, Christ Jesus, whom he made heir of life and eternity, and through whom he created the universe. The Word of God is personified by Jesus, God’s one, true, holy, and eternal Word. Et verbum caro factum est. This is the opening soliloquy in the Gospel According to John.

John is unique among his co-evangelists because his gospel is highly literary. It reads like any great work of prose only it was written by the finger of God, the author of Sacred Scripture. Like a master novelist God provides details throughout the story that foretell the mystery to be solved at the story’s conclusion, definitely a page-turner.

“How do you write?” an interviewer asked Stephen King. “One word at a time,” King replied. What words does the King use? One word—the Word.

The late novelist and writing teacher John Gardner taught that there are two kinds of stories: somebody goes on a journey; a stranger comes to town. Either way, a love story unfurls.

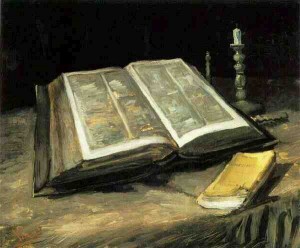

Stories and the words from which they are crafted give context and provide meaning. The entire Bible—all 73 books, all 783,000 words—comprises one narrative. It is the best-selling book of all time. It is the greatest story ever told.

Wordsmithing

The Bible is more than an epic, better than Beowulf, Moby Dick, or even the Thorn Birds! (I’ve been told that I look like Richard Chamberlin when I wear my cassock.) The Good Book contains characters, settings, and themes too numerous to unpack in a lifetime of homilies and I talk really fast. One of my bucket list items is to teach a class on every book in the Bible. To do that, I’ll have to live to be 117 years old, almost as old as Methuselah

The Bible is a love story, not unlike Ryan O’Neal and Ali McGraw, a tale of connection and disconnection between the Great Lover and his people. God is wealthy, powerful and privileged. We come from across the tracks. God is the love-struck protagonist who journeys from before time to the last days to bring his beloved people together. Right here. Right now.

The throaty and sensitive prophet Jeremiah spoke on God’s behalf: “For I have loved you with an eternal love and have continued my faithfulness to you” (31:3). Connected with the mystery of creation is the mystery of election, which shaped the history of the people of God dating back to Abrahamic times. God struck a covenant with the entire human family.

Action!

In the Book of Genesis the Lord God reveals his central desire: to live with his people in Paradise forever. We, the people are “a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation” (1 Pt 2:9). In the synagogue at Capernaum we sit at the feet of the Great I AM who feeds us with his body and blood because he loves us.

God planned the entire story before he belted it out on his typewriter. He tells Adam, “You are free to eat from any tree in the garden, except the tree of knowledge of good and evil. The moment that you eat from it you will die” (Gn 2:16b-17).

The forbidden fruit has now become the imperishable bread of life of which Jesus speaks in his super stellar sermons.

Wait! Adam and Eve disobeyed God. They missed their cues, the flubbed their lines. Didn’t they throw the story off course? The question now becomes, “Can God restore his relationship with humanity or is it sympathy for the devil?” It was just another day in paradise until the Lord took away Adam’s rib.

Vexing questions on this morning in America. All writing seeks to answer a question. This establishes the central conflict of the story. Novelist John Steinbeck, a writer who drew inspiration from the Bible, wrote, “All novels, all poetry are predicated upon the continual conflict between good and evil.”

A Journey of Eternal Miles

The Lord is kind and merciful, the psalmist claims. Despite our transgressions God continues to love us and longs for our return. He sent Abraham on a journey, telling him, “Leave your country, your family, and go to the land that I will show you” (Gn 12:1-3). This is Abraham’s faith walk.

What happens? The Egyptians enslave the Hebrews. The rising action of the story increases and things get worse for God’s people. He promises to free them and restore the Israel. He raises up Moses, a murderer, yet a man after God’s own heart, who guides them through the desert and across the Jordan River to dwell in cities they did not build and to reap harvests they did not sow.

Bitterness persists. Forty years. Nothing to eat but quail sandwiches. Oy, vey! God sent serpents for them to eat but the serpents ate them! Careful what you wish for.

The grass is always greener even though grass doesn’t grow in the desert. In Egypt they never had it so good: the fish, the bread, the garlic, the onions, the leeks, and the crocodile tails—tastes just like chicken. David thought it was a hoot and wrote a poem about it. Saint Paul was hopeful. “All ate the same spiritual food, for they drank from the same spiritual drink from the rock that is Christ” (1 Cor 10:3).

Scriptural Football

Exodus is the most important book in the canon of the Hebrew Scriptures. It sets a pattern of connection and disconnection that plays out for centuries. The Israelites (read: we) break faith with God. He exiles them, gives them a 70-year time out where they marvel at the hanging gardens of Babylon. Still they harden their hearts, subjecting themselves to greater hardship.

“They knew God but did not accord him glory as God or give him thanks. Instead they became vain in their reasoning, and their senseless minds were darkened” (Rom 1:21). If the light in you is darkness how great will the darkness be (Mt 6:23; Lk 11:35).

God appears aloof yet his desire remains consistent. He loves his holy, royal, priestly people. Surprise! The prophet Malachi received the gospel: “I am sending my messenger to prepare the way before me. Suddenly there will appear to you the Lord whom you desire” (3:31). Malachi hiked the ball and John the Baptist split the uprights.

He shoots, he scores!

Author! Author!

Enter the Messiah. A stranger comes to town. “What sort of man is this, whom even the wind and the sea obey?” (Mt 8:27). Jesus rose from the dead—he could do anything. He walked on water. Herpetologists named a lizard after him. His coming was foretold.

The Lord’s journey is difficult. “Who can accept this?” Peter denies the Lord and Judas betrays him. What’s up with that? No gratitude for having received First Holy Common hours earlier. It’s all good. Here the story of God reaches its zenith: the death and resurrection of our Savior. By his Paschal Mystery Christ defeats death, fulfilling his Father’s covenant with Abraham and reconciling the sins of the people. The central conflict is resolved.

In the epilogue a Jew from Tarsus is converted on the road to Damascus. Paul is charged with establishing Christ’s church on earth. He is another Moses, a prophet of the eternal covenant. Paul followed his bliss, commissioned for a long, strange trip to share the love, which, “bears all things, hopes all things, endures all things” (1 Cor 13:7). Give thanks to the Lord for he is good; his mercy endures forever.

The story of God is one of love and loss, heartbreak and deliverance, a romantic comedy in which all characters are to be reunited in the sequel, the Son of Man’s return. From Genesis to the Apocalypse the Bible is the greatest story ever told.

In Dante’s The Divine Comedy, Pontius Pilate earns himself the punishment of bearing the weight of the souls in Limbo. I leave you with his words: Quod scripsi, scripsi. What I have written, I have written.